The Canadian War Museum holds millions of objects in the National Collection. Each one tells a story.

This letter is more than 100 years old. It was written by a Canadian soldier — Private George Stonefish – and sent to his friend John Orvall Hubbell during the First World War. It is an example of how first-hand perspectives help us understand the human experience of war.

Private George Stonefish was a member of the Delaware First Nation from the Moraviantown Reserve, in Ontario. John Hubbell lived in nearby Thamesville. The two men sent letters back and forth throughout the war.

Stonefish wrote about everything, from the weather to food to his nightmares. He thanked his friend for sending tobacco and undergarments from Canada. The two traded stories about people from their neighbouring communities.

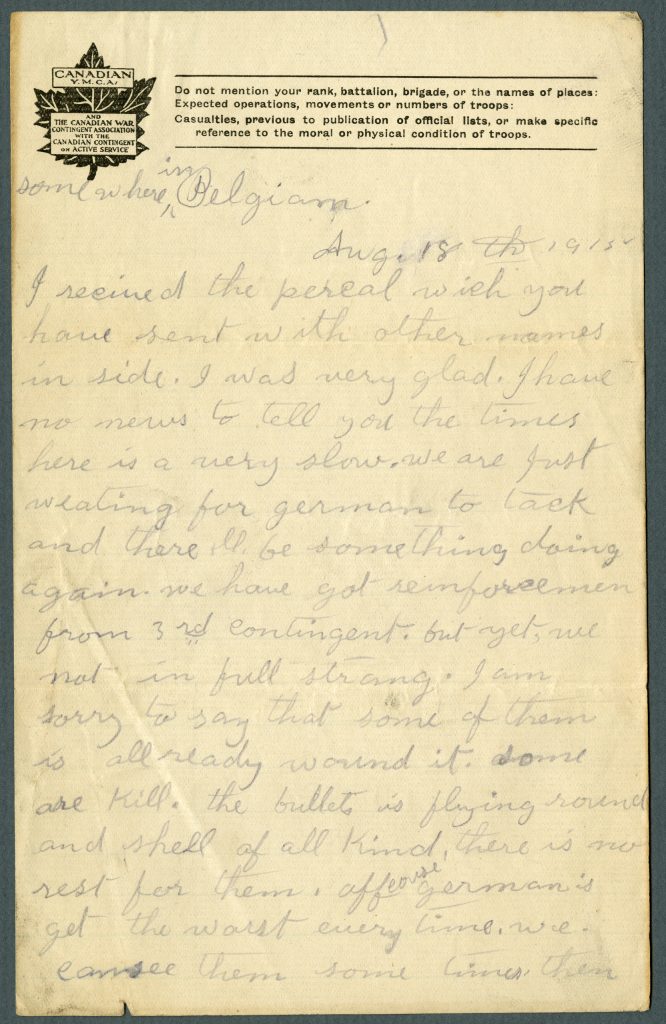

Stonefish often described the conditions at the front. “We are just waiting for Germans to attack,” he wrote in August 1915. While Canadian reinforcements had recently arrived, he noted that their introduction to the front was harsh: “I am sorry to say that some of them are already wounded. Some are killed. The bullets are flying round and shells of all kinds, there is no rest for them.”

In April 1916, he described returning from a nighttime patrol of no man’s land: “Just in time we jumped in our trenches and the shells burst behind the trench.” After this experience, where he nearly died, he seemed to accept his mortality, musing, “… if they don’t kill me here, I’ll have to meet my death anyhow someday.”

Soldiers had to be careful when describing their experiences to guard against military secrets falling into enemy hands. Warnings such as the one printed at the top of this letter served as stark reminders:

“Do not mention your rank, battalion, brigade, or the names of places: Expected operations, movements or number of troops.”

Stonefish fought at the deadly Second Battle of Ypres, in April 1915. A March 1916 letter to Hubbell hints that he might one day be able to tell him about the battle, but at the time all he could share was that he had been to Ypres before and was going again.

Letters were important for both people in Canada and those serving overseas. Letters from the front lines provided important insights into the war. For example, some of Stonefish’s letters home were published in the local newspaper.

For soldiers like Stonefish, letters from home were essential to morale and a crucial lifeline to the communities they had left behind.

The postal service was the only line of communication between families in Canada and their loved ones on the front lines. The Canadian Postal Corps was created in 1911 to move military mail. Throughout the First World War, Canadians sent approximately 85 million letters. It usually took two to three weeks for a letter to arrive at its destination.

Letters are significant sources because they were written by eyewitnesses to history, revealing unique insight into the human experience of war. In the case of the First World War, over 600,000 Canadians served, and tens of thousands of letters have survived. Each letter is unique; each tells us something about the men and women who served, including many who never came home.

Correspondence, like that between George Stonefish and John Hubbell, helps illustrate how soldiers and Canadians at home made sense of a global war that cost millions of lives. Letters also provide access to voices that are not always heard in official histories or government reports.

Like any source, letters should be read through a critical lens. They were authored by individuals who had their own unique perspectives. Writers 100 years ago, as today, selected information to include and to omit. They may have written in haste, or while upset or tired. Despite limitations, letters remain one of the richest resources for us to understand the past.

The Canadian War Museum holds thousands of letters in its archival collection.

One of the most important ways in which letters contribute to our understanding of the past is by giving us a glimpse of people’s emotions — their hopes and fears, their joys and sorrows. George Stonefish ended his April 8, 1916 letter by saying, “I will write again if I’m still alive.” A handful of words convey so much about what it was like to be a soldier in the First World War.

Stonefish did survive the war. At age 45, he was declared “medically unfit for further service” and discharged. After more than three years of service, he returned home in 1917 with a reputation as a highly skilled soldier.

Many First World War veterans struggled to return to their civilian lives. They had witnessed and carried out acts of brutality that were not easily processed. Some struggled with the guilt of having survived when so many comrades did not. Others were simply unable to settle down after the turmoil of the war years. Many veterans felt adrift, and often unable to speak about the trauma. All soldiers and nurses had their own war story; all veterans also faced their own challenges.

We are not sure about George Stonefish’s particular circumstances upon his return to Canada. What we do know is that he died of exposure near his home on February 17, 1920 and was buried in the Moraviantown Cemetery. His wartime letters remain a testament to his service.