Historical Overview

Historically, wherever geographic, economic and political factors dictated, the British Crown and other imperial powers in North America sought to include Indigenous allies in their military and strategic alliances. For their part, Indigenous groups and individuals either accepted, rejected or modified these overtures in accordance with their own objectives.

War and Indigenous Communities

From the First World War onward, military service by Indigenous people from Canada was contentious, and fraught with the potential for unintended outcomes.

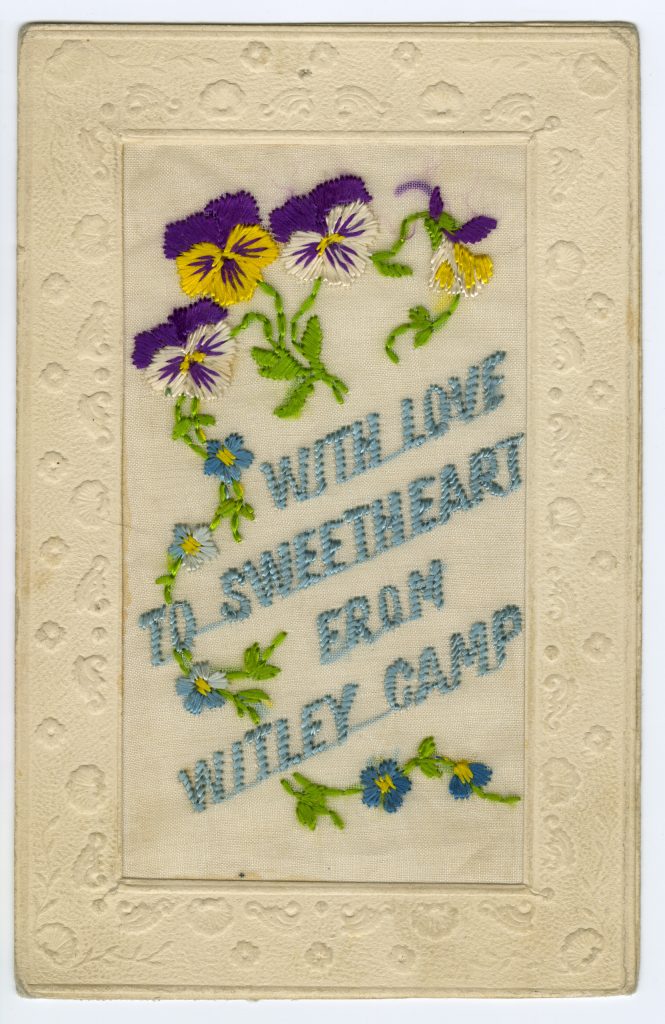

Combatants serving overseas risked death and injury. But for Indigenous families and communities, that was only one of several important problems associated with war.

Those at home faced family breakdown. Parents, older siblings and other role models and caregivers departed for war work or military service. This added to other upheaval, including the transfer of children to Indian residential schools, challenges to traditional political authority and the loss of Indian reserve lands through expropriation for military purposes.

During the Second World War, exporting food to allies overseas was a significant part of Canada’s war effort. To help meet the demand for food, some Indian residential schools were converted to food production. Indigenous children at those schools were forced into agricultural labour.

Today, for many Indigenous families across Canada, these twin legacies of multi-generational residential school attendance and military service are part of their lineage and their community’s history.

Indigenous Military Service

Indigenous people served in the Canadian military in both world wars and beyond. Many veterans returned to their communities after the wars and took on important leadership roles.

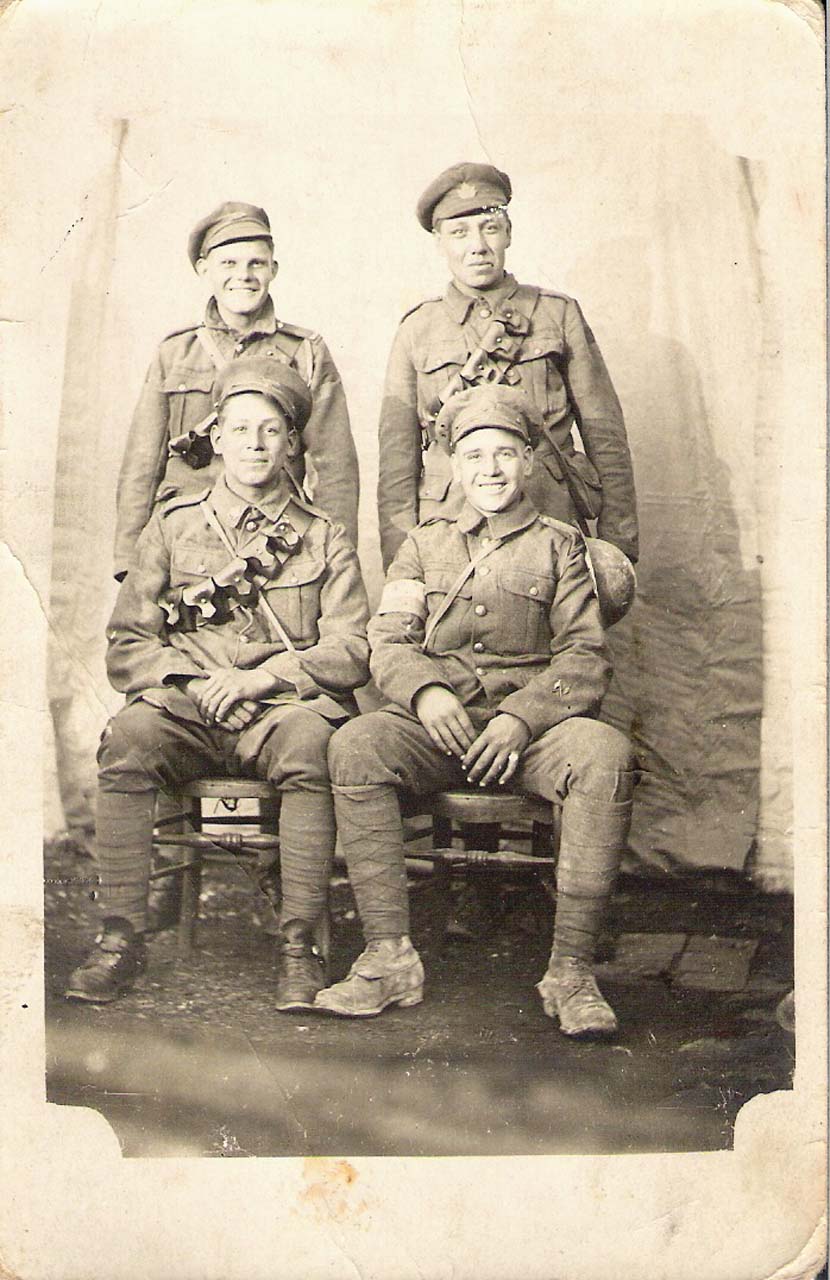

More than 4,000 status Indian men enlisted in the Canadian military during the First World War. An unrecorded number of non-status Indian, Métis, and Inuit men also served. The terms “status Indian,” “non-status Indian,” “Métis” and “Inuit” have different legal and cultural meanings, but all refer to Indigenous peoples.

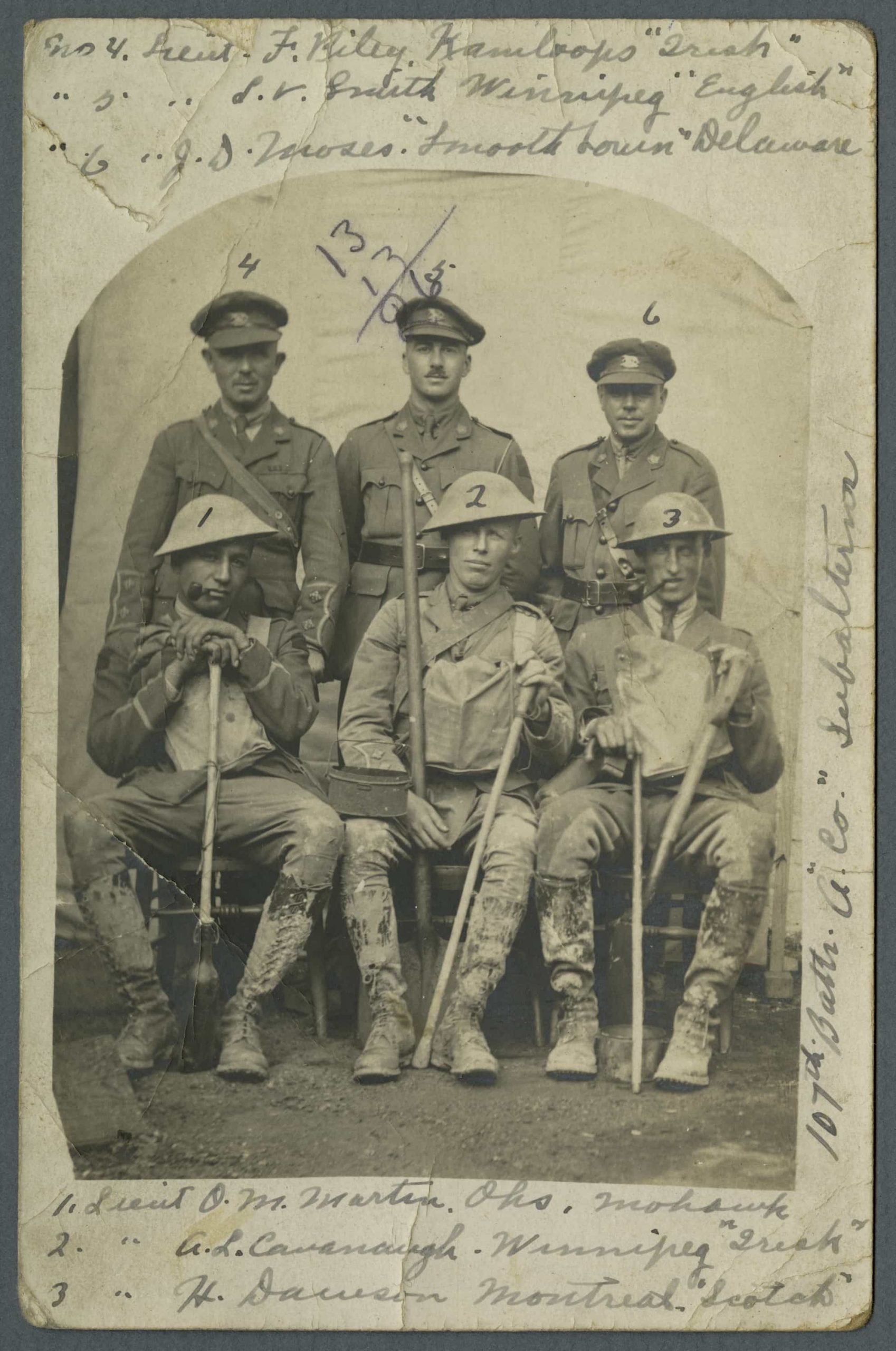

Canada’s two largely Indigenous formations of the First World War were the 107th “Timber Wolf” Battalion and the 114th Battalion (known as Brock’s Rangers). Both served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

During the Second World War, Canadians in all branches of the fighting services defended Canada or served overseas. Indigenous troops shared not only in the hard-fought victories, alongside their non-Indigenous comrades, but also in the defeats.

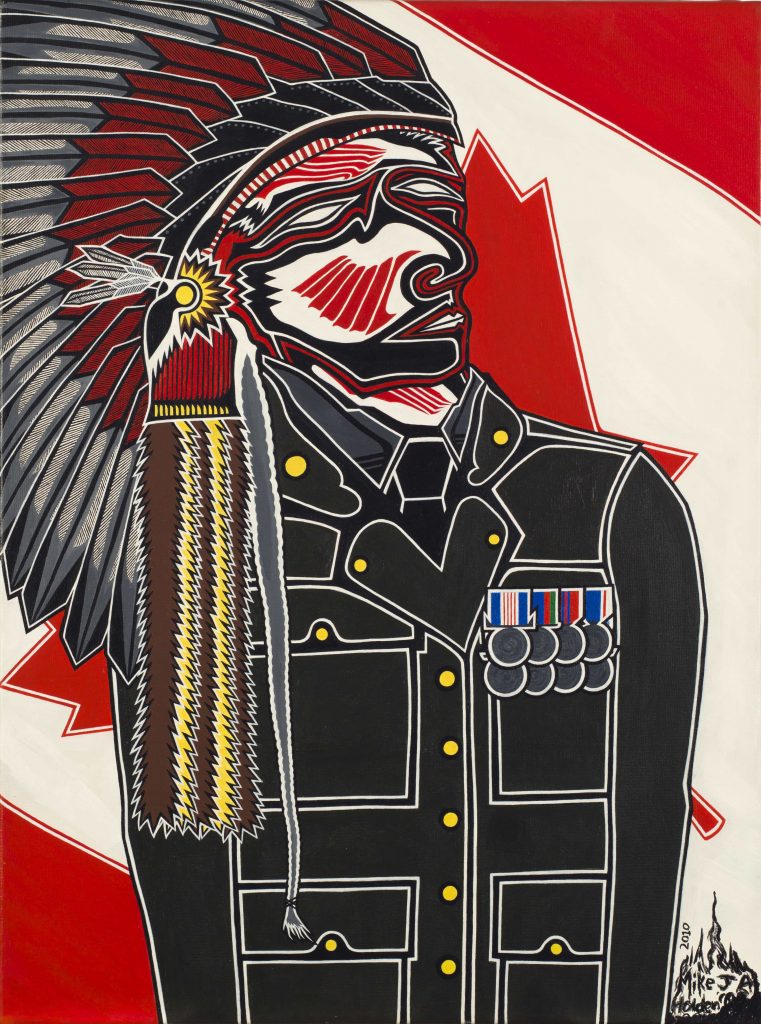

The wartime circumstances of Indigenous troops from Canada were unique. Those troops were denied the full rights and benefits of citizenship under Canada’s colonial Indian Act. Despite this, they were at the forefront in fulfilling that single most onerous and profound obligation of citizenship: donning the sovereign’s uniform and bearing arms against the nation’s enemies.

The Korean War saw the return to service of numerous Indigenous veterans of the Second World War. This was followed by the emergence of new generations of Indigenous servicemen and servicewomen, who participated in military operations worldwide. Indigenous people continue to serve in the military to this day.

Despite facing unequal treatment within society, Indigenous Canadians have served proudly in uniform in times of war and peace. Each person had his or her own reasons for enlisting, and those who survived often made their service known in the ongoing struggle for equality and to effect change in Canada.

Prepared by:

John Moses (Delaware and Upper Mohawk bands, Six Nations of the Grand River Territory)

Banner photo:

Members of the 107th “Timber Wolf” Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, during the First World War.

Courtesy of John Moses